Since the announcement of REACH LASAW, hundreds of people across the aviation sector – from air traffic regulators to safety auditors and consultants – have been paying attention and asking questions.

Intrigued experts want to know: how can the system detect aircraft, determine approaches and deploy warning alerts in all manner of specific applications.

This article goes into more specifics about how LASAW functions under the complex operating conditions of real-world airports and helipads. The key point is that LASAW is much more than a simple proximity threshold sensor.

As a new concept in early warning systems, it uses advanced algorithms to identify aircraft in specific sectors, predict flight behaviour and avoid “crying wolf” – especially in clustered landing zones.

As SkyNet Aviation CEO Jon Davis explains, LASAW’s unique intelligence detects complex aircraft approach vectors (and even specific instrument approaches) and arrivals that don’t meet various levels of specifically configured criteria.

“We designed it from the start not to generate high volumes of false alarms for applications like rig clusters or at multi-runway airports. We achieve this through custom defining the critical approach vectors,” he says.

“When we configure each site for you, LASAW will provide long-range monitoring for normal arrival vectors as well as a higher level of alert policy should aircraft approach suddenly from any direction.

“The key insight is that: yes, LASAW certainly does offer configurable proximity threshold alerts, but the main factors in its response initiation are proactive vector detection and complex flightpath analysis – not simply reactive alarms based on how close aircraft are.”

Designed to minimise false alarms

LASAW’s true power comes from the unique algorithms that assess which specific landing zone an aircraft is preparing to land at and initiating custom alert policies that are based on those assessments as well as rules set by the customer.

“As one of the major stipulations in the development brief, minimising false alarms was an issue we understood from the start,” Davis says.

“We had two major scenarios of ‘flightpath crowding’ on the board when we were prototyping LASAW: areas with multiple oil or gas rigs in close proximity and multi-runway airports – especially those with parallel runways.”

The solution SkyNet developed means that LASAW can determine which runway is being approached. Or, in the case of a cluster of rigs each covered by LASAW, a routine approach to one is not flagged as something unusual by the others nearby even though it’s technically outside their approach vectors while also within their proximity alert thresholds.

“Rest assured, LASAW returns minimal false alarms when correctly configured, adapted and continuously fine-tuned for specific locations.”

What’s more, aircraft that have landed or are departing do not trigger alerts. The reason is in the system’s name, Landing Approach Surveillance And Warning: the system was specifically built to watch out for incoming aircraft.

That means once an aircraft’s approach phase has been completed, LASAW de-lists it as a prospect for alert initiation. Regardless, LASAW will continue to monitor that aircraft: should it return to land after departure, such as in a circuit or emergency landing, LASAW will be ready to raise an approach alert.

How LASAW keeps an eye on runways

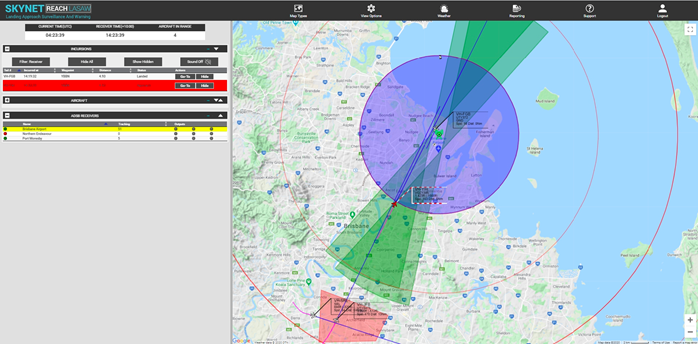

For airports with multiple runways, such as Brisbane Airport in the example below, LASAW is configured to pick up different early-detection vectors. These are shown in green on the image.

SkyNet REACH LASAW is PATENT PENDING

When an aircraft enters one of the green zones, LASAW determines if its performance metrics meet the specific conditions necessary for landing (as opposed to simply overflying). Commonly, this may be 0.4 nautical miles either side of the runway centreline – given that most aircraft approach using a stabilised approach method. In the real world, these green zones are cone-shaped “funnels of airspace” extending from the runway. In this case, the range is 10nm.

For LASAW to pay attention to an aircraft that enters the cone, its projected heading must fall within a customised set of allowances and other speed and rate of descent criteria.

In the example image, as well as the “green zone” of expected approach vectors is the blue zone, set here at 5nm (this can be altered to suit specific airports and can be any shape).

The blue radius is a detection area for aircraft that are circling before making an approach. Once again, the specific performance and vector conditions of these aircraft are monitored and LASAW only triggers an arrival alert when one enters a landing configuration.

For example, if an aircraft is circling and approaches from a downwind direction, then LASAW will not assess it as a landing aircraft until its projected heading vector falls within a custom angle, say 30 Deg of the runway centreline. While this form of approach has the shortest advance-warning time, it should still usually be around 2 minutes.

How LASAW keeps an eye on helipads

Unlike runways, which present physical limits on approach vectors, aircraft approaching helipads can potentially touch down from any point on the compass. Configuring LASAW’s approach monitoring for helipads is, therefore, more dependent on the expected approach vectors of incoming aircraft.

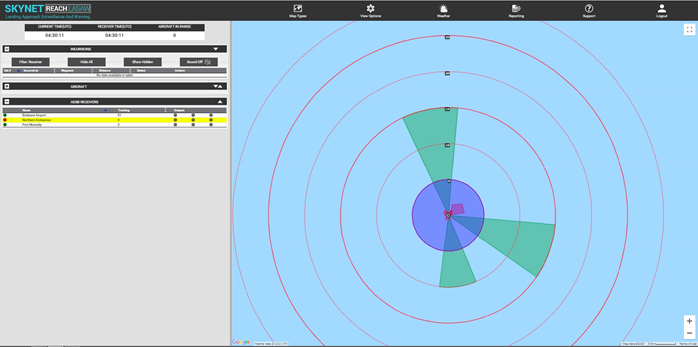

Below you can see a real-world example of LASAW configured for an FPSO facility and its no-fly zone (red) with multi-sector approach corridors highlighted in green at either 15 or 10 nautical miles.

SkyNet REACH LASAW is PATENT PENDING

Helicopters approaching along those green corridors are subject to routine LASAW alert policies. However, a helicopter in a landing configuration whose first contact with LASAW-monitored airspace is the blue zone (here set to a radius of 5nm) will trigger the non-routine approach alert policy that the facility operator has chosen.

“In visual conditions, helicopters approaching a helipad – especially at an oil or gas rig – generally all approach from a set flight path. If it’s bad weather and an instrument approach is required along a predefined track, that too can be added to the LASAW vector configurations,” Davis says.

“In the case of helicopters moving between closely placed rigs, LASAW can then be configured to monitor traffic from the direction of the other rigs nearby from which helicopters could approach.”

Rig clusters, instrument procedures and no-fly zones

Clusters of rigs present LASAW with unique operating parameters. In these situations, SkyNet recommends assigning multiple sectors to individual installations and for the instrument procedure flightpath to be overlayed and adjusted to a lateral distance as a custom variation.

This reduces the theoretical target threshold for rigs in the cluster and likewise reduces the occurrence of false alerts triggered by normal aircraft movements to those nearby facilities.

Further, most rigs have certain no-fly zones and no-approach sectors due to rig structures, outgassing and other restrictions. LASAW can geofence these areas and instantly detect if an aircraft has penetrated restricted airspace. If so, the system will instantly identify the aircraft, its registration and its operator so that a radio call can be initiated.

Autonomous and continuous equipment

While the LASAW system is powered by ingenious software, it still requires on onsite ADS-B receivers. Luckily, SkyNet has a wealth of experience in supplying industry-leading ADS-B equipment. These onsite LASAW emplacements have in-built redundancy systems and a component lifespan that extends into multiple years of 24/7 performance.

Fully self-contained, each LASAW emplacement requires zero user maintenance and is remotely monitored and updated as required by SkyNet’s in-house engineers. Each LASAW emplacement can also function completely independent of network connections. Even in cases where there is no data backhaul available, a LASAW emplacement can still calculate all flight intercepts and generate alert outputs by itself.

Find out how LASAW can be adapted to your needs

As you can see, the design brief of LASAW was to be flexible and customisable in providing the longest reliable and proactive alert time of aircraft approach with the lowest possible occurrence of false alarms. SkyNet simply understood from the start that operators needed to have the maximum confidence in what LASAW was reporting.

This is why you should see LASAW as an ongoing safety solution, rather than a one-and-done product. As flight routes change, new flight hazards are identified and improved landing facilities come into commission, SkyNet’s ongoing assessments and suggested changes will serve to maximise the performance of LASAW emplacements site by site. It’s all to keep your airspace more closely monitored and your landing zones safer.

To find out more about how LASAW – a new concept in approach warning – can work for your specific needs contact SkyNet Aviation. https://skynetaero.com/contact/

SkyNet REACH LASAW is PATENT PENDING